Explore the Mural: Notable Icons, Images & Landmarks

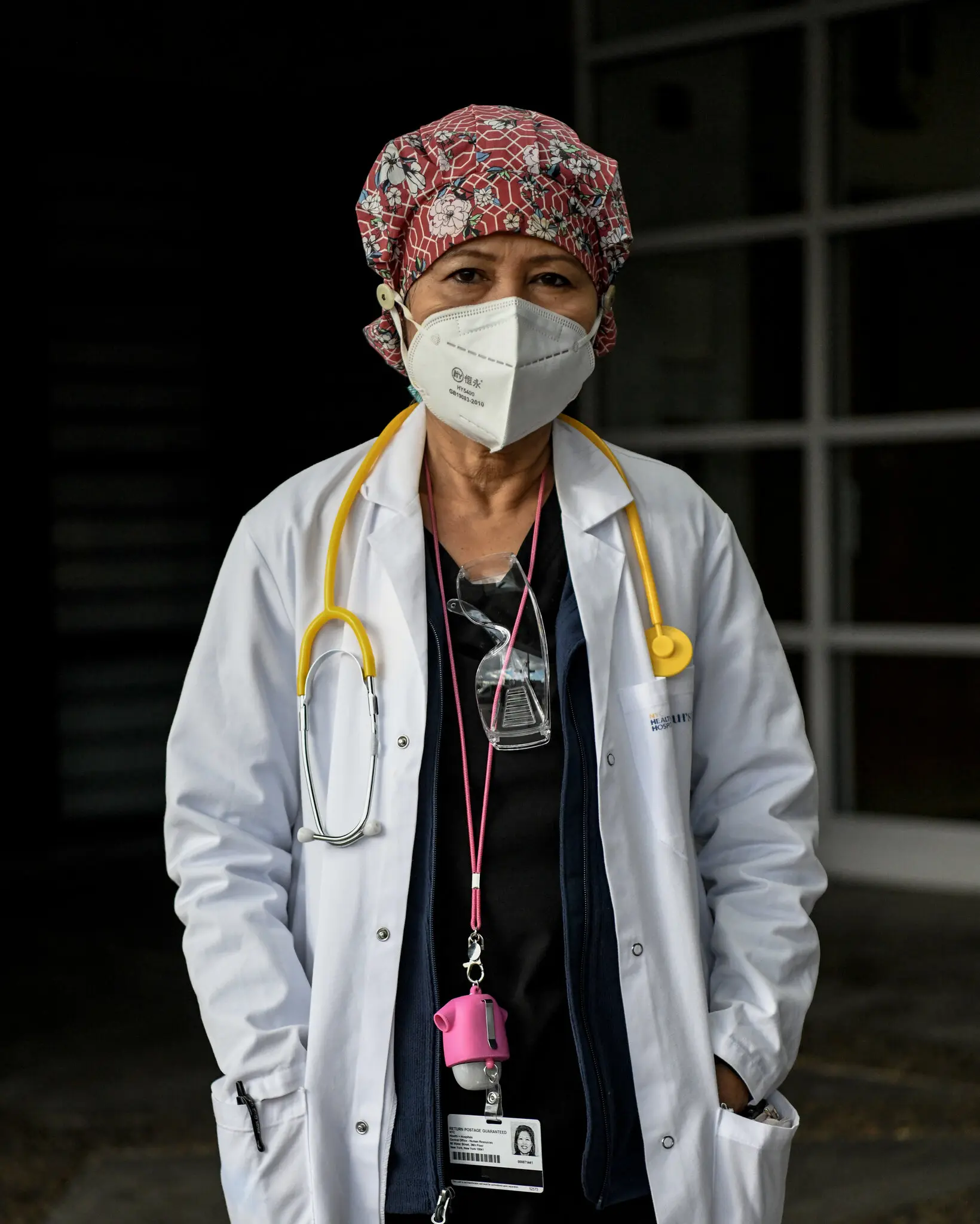

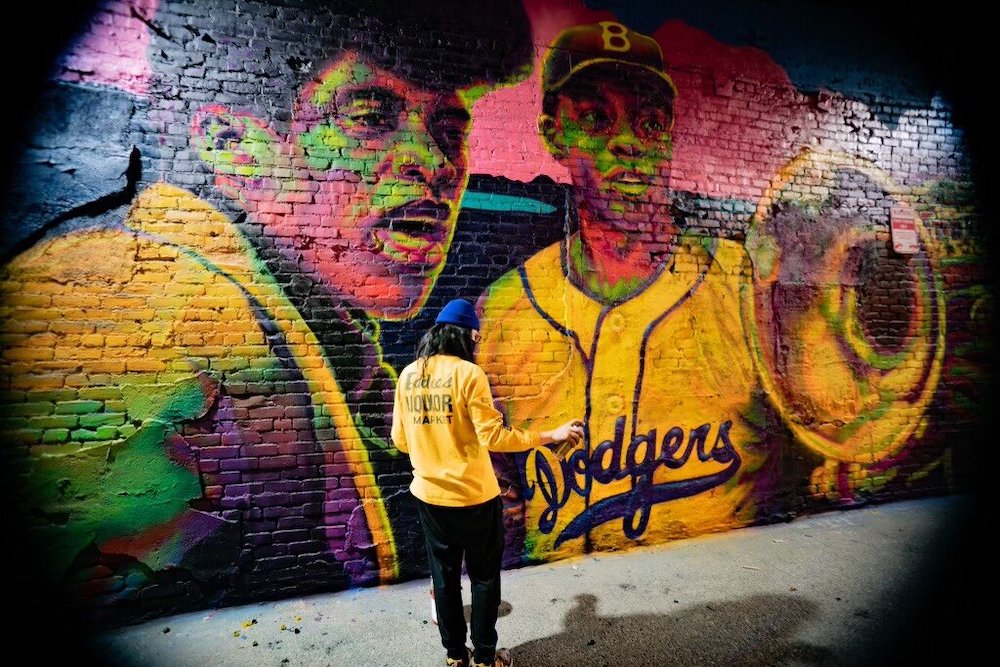

Photo by Jireh Deng

About Asian Pacific Environmental Network (APEN)

Asian Pacific Environmental Network is an environmental justice organization with deep roots in California’s Asian immigrant and refugee communities. Since 1993, we’ve built a membership base of Laotian refugees in Richmond and Chinese immigrants in Oakland. Together, we’ve fought and won campaigns to make our communities healthier, just places where people can thrive.

But our work is not only local. Our members have always lifted up the importance of making connections with other frontline communities and the need for organizing more people to build power for Asian immigrants and refugees. Our members recognize that our local neighborhoods are impacted by decision-making happening not only at the local level, but also at the state level.

That is why APEN is also deeply invested in building power across the state. Since 2012, we’ve engaged in statewide power building efforts, like talking to Asian voters statewide about critical Environmental and Economic Justice issues.

Through deep conversations with our members and partners, it became clear that we needed to invest in deeper organizing in another region in order to realize our vision and make meaningful impact and continue to deepen our roots and build power for working class Asian immigrant and refugee communities.

Los Angeles represents a unique and dynamic opportunity for APEN to build a deep impact in Asian immigrant and refugee communities around environmental justice issues.

Team APEN in the South Bay!

AAPIs in the South Bay

Our community art project is aimed at telling the story of Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities in the South Bay — their history and their hopes. AAPI communities have a long history connected to the South Bay.

The earliest enclave of Chinese in Los Angeles centered around Los Angeles Plaza (El Pueblo de Los Ángeles), the original settlement of the City of Los Angeles, bounded by North Spring Street, Cesar Chavez Avenue, Alameda Street, and Arcadia Street. Chinese farmers were a visible and important part of the Los Angeles economy through the twentieth century and established themselves as a powerful political group. The earliest farms were small plots surrounding Chinatown. As Chinatown developed into a populous residential and commercial center, Chinese entrepreneurs moved to farms outside of the urban center, migrating westward toward Santa Monica Bay, and southward to South Los Angeles and the communities of Watts, Wilmington, and San Pedro.

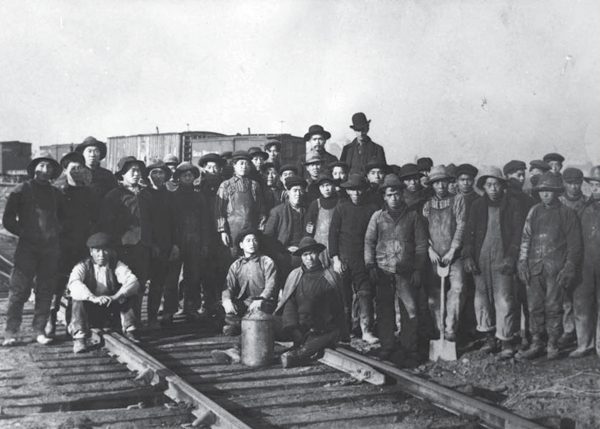

In 1885, Japan legalized the emigration of labor and Japanese were recruited to the United States to fill railroad jobs previously held by Chinese immigrants since barred by the Restriction Law of 1882, or Chinese Exclusion Act. In addition to filling the gap created by the lack of Chinese laborers, the demand for labor in Southern California increased due to rapid industrial expansion. As a result, not all Japanese took positions with the railroad. Similar to the Japanese, Filipino immigration to Southern California was influenced by the Chinese Exclusion Act and its later extensions. Because the Philippines was under American colonial rule from 1898 to 1946, these exclusionary immigration policies did not apply to Filipinos. As such, Filipinos were targeted to meet labor shortages in Hawaii and California.

In 1903, Terminal Island’s first and only cannery at the time, California Fish Co., perfected a method for canning tuna in order to market it as an affordable substitute to chicken. With expertise from their home region of Wakayama, Japan, the new Japanese settlers soon proved to be master commercial tuna fishermen. Word spread quickly back to Japan of the success to be had at Terminal Island, and by 1907 an estimated 600 Japanese fishermen operated out of the area. This wave of immigrants came mainly from the Wakayama and Shizuoka areas, via San Francisco and Seattle.

Not long afterward, the Japanese single-handedly created California’s tuna fishing industry. Albacore tuna had never been caught commercially in California prior to the introduction of the hook-and-line method that Japanese fishermen began employing in 1912-13. According to author Naomi Hirahara, “3,000 Japanese lived at Terminal Island or Fish Island in some 330 houses almost identical in size and appearance except for long houses designed for multiple occupants.” The residences were typically two-bedrooms with a porch and a small fenced-in yard, and rented for $6 per month. Bungalows were located along Tuna Street and Terminal Way. The fishing village also included a school, churches, and community meeting centers for social and sporting events.

Cannery workers were typically Filipino men and the Japanese women who came to the village as picture brides. None of the canneries remain. Most Filipinos on the West Coast became migratory laborers, traveling throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, following harvest and canning seasons. Filipinos who settled in Los Angeles year-round found work as house servants, janitors, dishwashers, bus boys, and other jobs in the service sector. Most of the significant resources associated with Filipino American history in Los Angeles were found in the Temple-Beverly and Wilmington areas. These areas have been the largest and longest-continuously populated of the known Filipino American neighborhoods in Los Angeles.

During the 1920s to the 1940s, the largest concentration of Filipinos outside of Little Manila was found in the Los Angeles Harbor area, especially around West Long Beach, San Pedro, and Wilmington. Early Filipinos who had completed their military service settled in areas near Navy ports. From 1919 to 1940, the U.S. Navy Battle Fleet’s Home Port was in San Pedro. By the 1920 Census, one-fourth of Filipinos in Los Angeles worked in various shipyard occupations at the Port of Los Angeles and lived in San Pedro and Wilmington. In the wake of the removal and forcible incarceration of Japanese Americans on the West Coast during the war, many Filipinos were recruited to fill the labor vacuum left by Japanese agricultural workers.

Following the war, many Filipinos returned to their old neighborhoods in San Pedro and Wilmington, where they found work, housing, and a sense of belonging. In 1945, Filipinos living in San Pedro, Wilmington, and Long Beach formed the Filipino Community of Los Angeles Harbor Area, Inc., and one year later pooled their resources to build a community hall at 323 Mar Vista Avenue in Wilmington to provide a community gathering place for Filipinos in Los Angeles for decades to come.

The Samoan community in Los Angeles County has its roots in a group of Samoan-born men who were enlistees in the U.S. Navy. When authority over the six islands that make up American Samoa was transferred from the Navy Department to the Interior Department in 1952, 300 men dubbed the Fita Fita–the Island’s native Navy contingent–were given the option of transferring to Hawaii. Almost all of the Fita Fita emigrated. Their dependents , about 1,000 women and children, were allowed to join them in Hawaii in a voyage that has gained some infamy among Samoans. Later, many of the Fita Fita were posted to the West Coast, and they brought their dependents with them to settle near Navy bases. By the time Carson incorporated in 1968, a large Samoan community had taken root there.

California is home to the largest concentration of Samoans on the mainland United States. Many of the new immigrants, largely driven from the U.S. territory by poverty, have settled in Carson, Compton and Long Beach.

Today, AAPI communities who have settled in Los Angeles’ South Bay Region face a unique and pressing challenge. Residents live against the backdrop of rail lines, freeways, oil wells, smokestacks, industrial storage tanks and the constant flow of trucks moving goods throughout the West and beyond. As a result residents who live in the region are at higher risk of cancer, asthma and other respiratory illnesses as compared to the rest of LA County.

The good news is that our community has and is fighting for a more just reality. Community members have organized to stop the expansion of refineries in their neighborhoods, they’ve fought and won to phase out oil and gas drilling across LA County and are continuing to fight for a clean and healthy environment where they can live, work, learn, plan and thrive.

APEN staff painting the AAPIs in the South Bay mural.

About the Artist: Bodeck Luna

An immigrant artist from Manila, Philippines, Bodeck Luna creates pieces that explore the relationship between nostalgia, social empowerment, and decolonization. His background in street art heavily influences his figurative paintings, illustrations and murals. Some of his notable collaborations include Apple, LA Metro, Long Beach City Hall, Music Center LA, Aquarium of the Pacific and Covered California.

Bodeck showcases paintings, murals and curates other artists’ pieces in pop-up art shows throughout the city to display other emerging artists. Bodeck was appointed as the Art Director for the first annual Long Beach Filipino Festival in 2018. From commercial and private commissions to album covers, he aims to bind the community by showcasing local talent and businesses.